A Stone's Throw From Glory

My report from the Kentucky Stone Skipping Invitational

There are a number of reasons why the piece I’m sharing with you today is not a proper piece of sports journalism.

First of all, it’s not objective: I’m writing about an event wherein the organizer and several of the competitors are good personal friends. Second, I didn’t do a bunch of background research, nor did I actively solicit quotes from the competitors. Third—and I feel like this one is really important—I hadn’t even planned to write about the event when I showed up; I was just showing up to support my friends.

Fourth? Well, I decided to compete in the event myself.

With all of those caveats now on the table, I’d like to tell you about my experience at the Second Annual Kentucky Stone Skipping Invitational, an event that took place this past weekend on the banks of Lake Shelby in Shelbyville, Kentucky.

The event—organized by Jon Jennings, a Kentucky native, professional stone skipper, and (as previously noted), good friend of mine—drew a field of competitors from both locally and far afield, with attendees having trekked in from as far as Texas and California to skip stones on a muggy, overcast Kentucky afternoon. Among those competitors was Kurt “The Mountain Man” Steiner, a Pennsylvania native who’s received coverage in numerous media outlets for his stone-skipping exploits, which include the current world record of 88 skips on a single throw.

Okay, so to be clear—you are talking about skipping stones, like we did as kids, right?

That’s correct!

Now, there’s a temptation when writing about niche competitions like this as an outsider to approach them comically and/or derisively—what do you mean there’s professionals doing that?—and I can tell you that a great way to disabuse yourself of that notion is to jump in and get humbled doing it yourself. Watching Steiner and the other invited professionals warm up was a bit like stepping onto the track with Olympic sprinters. Their first few practice throws skipped nearly to the opposite bank with ease, setting the tone of the competition for any potential doubters.

Oh. I cannot do *that*.

The event was an invitational, but there was an open division as well, one that drew some clearly-practiced-but-as-yet-unknown-on-the-scene skippers, as well as a handful of “yeah what the heck, I’ll give it a go” entrants from a nearby campground. The entry fee was modest, and despite it being a good handful of years since my latest organized athletic event (and having almost no experience skipping stones as an adult) I decided to join. When in Rome, y’know?

“I’ll put you in the Regular Men division,” the man working the sign-up table noted.

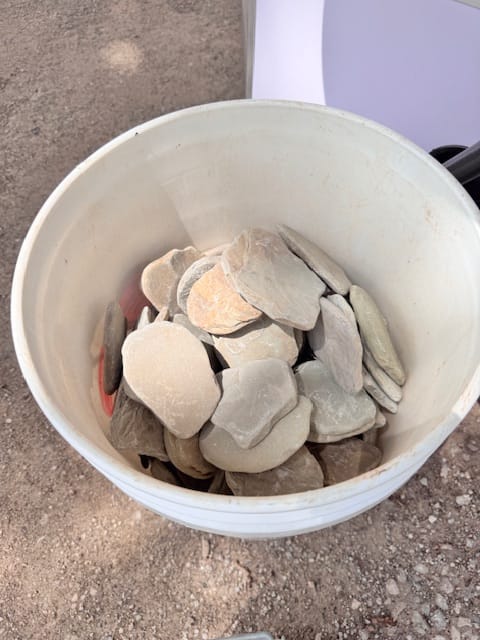

“That’s nice of you to say,” I thought, and then signed up as “Action Cookbook” anyways. (The sign-up sheet already included someone who’d entered as “Banana Man”, so I felt like I was in a safe place1.) I paid five dollars for a half-dozen stones from a bucket under the table, and began visualizing my certain defeat.

We’d arrived early, which gave me time to do some base-level research on The Many Questions You May Have About Professional Stone-Skipping, most of which I pried out of Katie White, my good friend and organizer Jon’s wife.

(I also bought a fried bologna sandwich from a food truck, because you can’t compete at a high level without proper fuel.)

What are the rules of competitive stone-skipping?

This was the first thing I had to know, and as it turns out, there’s no consensus. The sport has no overall governing body, and so the rules of competition—while usually somewhat consistent—are officially set by each event’s organizer. In this particular event, each competitor would get six throws. The primary objective would be to attain the single best individual throw (as determined by number of skips), with the cumulative total across all six skips used for a tie-breaker, if needed.

“It varies by region,” White explained, as my son dragged her son through a patch of mud along the bank2. “In the US, it’s all about number of skips. In Europe, they call it ‘skimming’, and it’s about total distance. In Japan, it’s more about style.”

(Great. I already want badly to go to a Japanese baseball game, now I’ve got two sporting events I need to book an expensive flight for.)

How do you determine the total number of skips?

This wasn’t immediately clear to me, because each throw happens so fast.

There are, of course, technological solutions available; Steiner’s world-record throw was confirmed via multiple camera angles and through consultation with a college physics professor. In normal competition, though, it’s done entirely by eye. A panel of three judges conferred briefly after each throw, settling on a number in roughly the same manner that Olympic skating or gymnastics judge might give a score.

“When you see enough of these, you know what to call them,” White noted, adding that the first few skips of the day tend to set the metric for the event. I imagined this to be similar to how baseball players adjust to an umpire’s strike zone, and also figured there was no chance that my winning or losing would come down to a judgement call.

What kind of stones do you use?

The only hard-and-fast rule about the stones is that they must be naturally-formed; you can’t shave, shape or otherwise manufacture stones for competition.

The best stone for throwing is a flat, roughly palm-sized stone with as least one corner to grip when throwing. “A diamond shape is good.”

“That’s a good stone,” Steiner remarked in passing as I picked one out of the bin for sale, and I felt both a swell of pride for my innate taste in stones and a fluttering of optimism for my chances. (Maybe I’m a natural!)

Where do you find the stones?

“Don’t ask her that!”, my wife interjected, afraid I would divulge a secret quarry to my many readers, thus blowing up Jon’s spot.

“I meant generally,” I clarified, well aware of the immense responsibility I bear as the writer of a niche-beloved general-interest email newsletter.

The answer, generally speaking, is around the banks of the Great Lakes, with flat, soft stones like slate and shale typically the best-performing. “Jon sometimes uses Kentucky limestone, but that’s more of a sentimental choice.”

What’s the best technique for throwing?

I asked this question of Jon directly, fully aware that this is like asking Paul Skenes how to throw a baseball. There’s a big difference between knowing and doing, but I at least wanted to not embarrass myself in front of my children, or at least not any more than I would on a typical Saturday.

Competitors use a variety of motions, much like the range of deliveries that Major League pitchers display; one of the pros employed a sharp downward arm motion with an outward wrist-flick at the end so abrupt it seemed impossible that his stones weren’t sinking right at his feet. Generally, though, it’s best to use a forehand throw with the index finger positioned to spin the stone horizontally at the moment of release, aiming to strike the water with a 10-15 degree upward tilt.

As the competition neared, I tensed up a bit, though that might have also been the gigantic fried bologna sandwich I’d eaten an hour prior. A playlist of ‘90s country hits competed with the intense drone of cicadas3, and a few stray kayakers and anglers had to be shooed away before the pros would go. An eight-year-old girl competing under the name “Awesome Blossom” led off the children’s division, and—

Quit stalling, Scott. Tell us how you did.

Not terribly, to my pleasant surprise!

I didn’t “kerplunk” a single throw—the accepted term for a stone that doesn’t skip at all—and my best throw went for thirteen skips:

This was just good enough to be better than the best child, which is genuinely all I ask for in any athletic competition these days. I placed seventh in the open division and settled into my camp chair, relieved and ready to watch the pros go for glory.

Unlike the amateurs, who took all six throws at once, the pros rotated two throws per turn. This allowed their arms to rest and presumably gave them a chance to adjust as they observed other’s results. No world records were broken, but their throws easily put my just-happy-to-be-here effort to shame.

Twenty-eight. Thirty-two. Thirty-five. Thirty-six.

In the end, Aidan “The Wizard” Woolsey, a competitor from upstate New York, narrowly edged out Californian Kyle “RockSkippingPro” Graff and Steiner for victory in an top three separated by a single skip each.

It was a fun, congenial event, and a great way to pry my kids away from video games on a Saturday afternoon. Having realized halfway through that I was not going to be able to resist the temptation to write about it, I tried to at least resist my tendency to force a deeper meaning onto it. It was fun to watch—fun to see people competing at the top level of their sport, even if it’s a sport that many people aren’t aware exists. It was fun to compete against them, even if my chances of winning were no less foretold than when I ran the New York City Marathon years ago.

It didn’t have to have any deeper meaning.

Of course, then White accidentally dropped a perfect kicker line on me, as we reflected on the dedication that Jennings and others give to their lesser-known sport.

“Anything practiced enough can be an art form.”

—Scott Hines (@actioncookbook)

By the time the event had started, however, Banana Man was nowhere to be found. Where have you gone, Banana Man? Our nation turns its lonely eyes to you. ↩

Willingly, I should note. I actually think it was his idea. Frankly, not my business either way. ↩

Tim McGraw’s “Something Like That” mentions stone-skipping in the first verse, making it an obvious choice for the leadoff song. ↩